SAINT AUGUSTINE'S, GRAHAME PARK

ICONS FOR CONTEMPLATION

Manuel II Palaiologos, Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment, Constantinople, 1309-11. In 1261, the Byzantine empire's power and its church were restored by Manuel II Palailogos. Previously, the city fell in 1204 to the Fourth Crusade, and more than nine hundred years of artistic and cultural traditions were abruptly terminated (The Latin Empire was established and the first Latin patriarch was installed.)

What is of interest for us in this image is the expression of how profoundly the person (a leader of a country) was immersed in his Christian culture. The Ruler is himself being ruled.... The scepter with the cross, the symbol of his power, shows this 'intermingling of rules'. The Emperor is subject to Christ, and his respect and honor to the realm of Divine Grace is beautifully expressed in the gentle gesture of holding the sceptre.

I just wonder how a portrait of ours would depict how we are submersed in and shaped by the powers of our culture today. In this imaginary icon, would our features show the same peace of Christ - or the lack of beauty, our being torn apart by the forces of cyber space, politics, and consumption would dominate?

What is of interest for us in this image is the expression of how profoundly the person (a leader of a country) was immersed in his Christian culture. The Ruler is himself being ruled.... The scepter with the cross, the symbol of his power, shows this 'intermingling of rules'. The Emperor is subject to Christ, and his respect and honor to the realm of Divine Grace is beautifully expressed in the gentle gesture of holding the sceptre.

I just wonder how a portrait of ours would depict how we are submersed in and shaped by the powers of our culture today. In this imaginary icon, would our features show the same peace of Christ - or the lack of beauty, our being torn apart by the forces of cyber space, politics, and consumption would dominate?

ON MARY'S VIRGINITY

(The icon of the 'Sing)

‘The Virgin trusted in the Lord; though she gave birth to the Word become man, she remained a virgin always. We praise her and say: Blessed are you among women.’ (Benedictus antiphon, Second Sunday after Christmas)

In the Catholic tradition, Mary’s virginity leaves all ages puzzled. The ‘whys’ can lead us to diverse directions. Yet, this remains the profoundest, ‘existentially’ most deeply rooted truth of faith. Just like in icons the person of Mary is never represented without her son, Jesus, Mary’s virginity is inseparable from the truth of Christmas, the fact and why of the Incarnation. Mary’s virginity can be contemplated as humankind’s deepest desire for bringing peace into History.

Consciously or unconsciously, we know that every birth is connected with the underlying streams of human history, violence. Every individual, at the very moment of his or her conception is marked by the close or distant presence of aggression, misunderstanding, and war. We are born, however, not only into this collective history of ‘lack of peace’. As individuals, we are also marked with the presence of these destructive energies, deeply present in our family histories, nay in our individual psychological history.

Thus, the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary is a parallel existential statement with that of faith. As our deepest desire, we want to revert the negative stream of violence in history! This remains our permanent call. Actually, it should be part of everyone’s vocation and purpose in life.

In our icon, the red mophorion (shawl) of Mary, is profoundly symbolic. Just like her, we should be mantled with this ‘gown of virginity’. When contemplating this icon, we can pay particular attention to the harmonic folds of this red mantle-veil. Projecting our self under it, we can feel the transforming presence of the doctrine of the virginity. The three stars on Mary’s shoulders and forehead, embroidered into the shawl, glister forth as our ability to bring peace into history and into our personal existence.

‘The Virgin trusted in the Lord; though she gave birth to the Word become man, she remained a virgin always. We praise her and say: Blessed are you among women.’ (Benedictus antiphon, Second Sunday after Christmas)

In the Catholic tradition, Mary’s virginity leaves all ages puzzled. The ‘whys’ can lead us to diverse directions. Yet, this remains the profoundest, ‘existentially’ most deeply rooted truth of faith. Just like in icons the person of Mary is never represented without her son, Jesus, Mary’s virginity is inseparable from the truth of Christmas, the fact and why of the Incarnation. Mary’s virginity can be contemplated as humankind’s deepest desire for bringing peace into History.

Consciously or unconsciously, we know that every birth is connected with the underlying streams of human history, violence. Every individual, at the very moment of his or her conception is marked by the close or distant presence of aggression, misunderstanding, and war. We are born, however, not only into this collective history of ‘lack of peace’. As individuals, we are also marked with the presence of these destructive energies, deeply present in our family histories, nay in our individual psychological history.

Thus, the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary is a parallel existential statement with that of faith. As our deepest desire, we want to revert the negative stream of violence in history! This remains our permanent call. Actually, it should be part of everyone’s vocation and purpose in life.

In our icon, the red mophorion (shawl) of Mary, is profoundly symbolic. Just like her, we should be mantled with this ‘gown of virginity’. When contemplating this icon, we can pay particular attention to the harmonic folds of this red mantle-veil. Projecting our self under it, we can feel the transforming presence of the doctrine of the virginity. The three stars on Mary’s shoulders and forehead, embroidered into the shawl, glister forth as our ability to bring peace into history and into our personal existence.

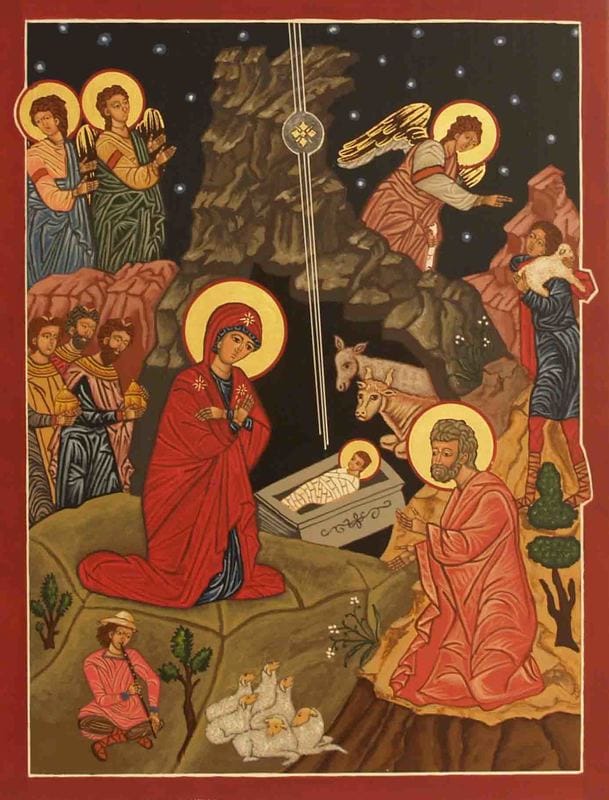

THE ICON OF THE NATIVITY

Our Dialogue with the Divine Harmony

This ‘anonymous’, seemingly unremarkable icon gently shares with us its message. The rays of the star, like a ruler, with determination, point to the child. Three thin lines, yet a firm strength over against the dark background. This new Born Saviour, however defenceless he is, creates an equilibrium and harmony in our world of shaken order. These rays arrive not vertically, but in a gentle angle, highlighting the Divine Power which alone can hold the world together.

The second striking feature of this icon is the shepherd to whom the Angel is turning. This can be not only a male shepherd but a female shepherd! Perhaps, the icon’s message is the invitation to identify with this shepherd. She or he is humble and simple, but a fully erect human being. One should not overlook how the angle of the body is perfectly in tune with that of the Three Divine Rays. This axis of harmony is fully absorbed by the shepherd. His/her call, ‘the vocation’, the ‘graced’ purpose in life indeed makes us fully erect: physically, morally, spiritually. Nourished by this Harmony of the Incarnation, we become seers of angels.

The lamb on the shoulder of the shepherd, in this latter context, means something more than ‘sheep’. Its whiteness and closeness to both the human intellect and the heart is a symbol of contemplated life; our work contemplated on. In the strictest sense, it is one’s own spirituality. One’s own effort to understand his or her particular life-situation in the light of Revelation.

I would like to apply a thought from the Chasidic mystical work, Tanya, to the figure of the shepherd as the ‘our spiritual icon’. The author of the book says that angels do not have the power to elevate the fallen world. It us only us humans, terrestrial beings who can do that for we are vested in a material body. This Chasidic thought can be read when looking at the relationship between the Angel and the shepherd. The shepherd is indeed a ‘terrestrial being’, so deeply one with nature, expressed by the embrace of the rocks. A puzzling thought, indeed, to follow the Chasidic ‘anthropology of grace’. Namely, it is humans’ privilege and unique ability to restore the divine sparks of creation. Angels cannot do this work because they are outside matter. That is why the celestial beings come to hear novelties of our understanding of the Scriptures from the terrestrial beings, what they discover and reveal of the secrets of wisdom which until then were in bondage, in exile…

This thought of Jewish mysticism is perfectly in tune of what we Christians believe about angels. When, like the shepherd, one develops a spirituality, processing Revelation, Angels appear with their supportive power. They do not resolve our problems, but they can function as our aides. Classic Catholic theology calls it ‘God’s helping grace.’

This kind of ‘angel-human’ relationship aptly speaks of the Revelation which took place on the first Christmas Eve. I like reading this appearance of Truth in terms of the above dialogue. Is the angel revealing the arrival of the Messiah out of blue? I do not think so. This powerful good news was already present in those shepherds’ yearnings for the Messiah. Their ‘spirituality’, their effort to let this yearning emerge to a full pilgrimage to the Crib, was the first step. The celestial beings ‘came to hear novelties’ of their Biblical advent. Actually, all of us, angels and humans; and animals, and other inanimate beings are joining in God’s own ‘spirituality’. That is, we gather around his reading and creating the ‘fullness of time’; his judging of the human condition; and his effort to make the Incarnation come about… On this holy eve we all share the role of interpretation of the Nativity.

This ‘anonymous’, seemingly unremarkable icon gently shares with us its message. The rays of the star, like a ruler, with determination, point to the child. Three thin lines, yet a firm strength over against the dark background. This new Born Saviour, however defenceless he is, creates an equilibrium and harmony in our world of shaken order. These rays arrive not vertically, but in a gentle angle, highlighting the Divine Power which alone can hold the world together.

The second striking feature of this icon is the shepherd to whom the Angel is turning. This can be not only a male shepherd but a female shepherd! Perhaps, the icon’s message is the invitation to identify with this shepherd. She or he is humble and simple, but a fully erect human being. One should not overlook how the angle of the body is perfectly in tune with that of the Three Divine Rays. This axis of harmony is fully absorbed by the shepherd. His/her call, ‘the vocation’, the ‘graced’ purpose in life indeed makes us fully erect: physically, morally, spiritually. Nourished by this Harmony of the Incarnation, we become seers of angels.

The lamb on the shoulder of the shepherd, in this latter context, means something more than ‘sheep’. Its whiteness and closeness to both the human intellect and the heart is a symbol of contemplated life; our work contemplated on. In the strictest sense, it is one’s own spirituality. One’s own effort to understand his or her particular life-situation in the light of Revelation.

I would like to apply a thought from the Chasidic mystical work, Tanya, to the figure of the shepherd as the ‘our spiritual icon’. The author of the book says that angels do not have the power to elevate the fallen world. It us only us humans, terrestrial beings who can do that for we are vested in a material body. This Chasidic thought can be read when looking at the relationship between the Angel and the shepherd. The shepherd is indeed a ‘terrestrial being’, so deeply one with nature, expressed by the embrace of the rocks. A puzzling thought, indeed, to follow the Chasidic ‘anthropology of grace’. Namely, it is humans’ privilege and unique ability to restore the divine sparks of creation. Angels cannot do this work because they are outside matter. That is why the celestial beings come to hear novelties of our understanding of the Scriptures from the terrestrial beings, what they discover and reveal of the secrets of wisdom which until then were in bondage, in exile…

This thought of Jewish mysticism is perfectly in tune of what we Christians believe about angels. When, like the shepherd, one develops a spirituality, processing Revelation, Angels appear with their supportive power. They do not resolve our problems, but they can function as our aides. Classic Catholic theology calls it ‘God’s helping grace.’

This kind of ‘angel-human’ relationship aptly speaks of the Revelation which took place on the first Christmas Eve. I like reading this appearance of Truth in terms of the above dialogue. Is the angel revealing the arrival of the Messiah out of blue? I do not think so. This powerful good news was already present in those shepherds’ yearnings for the Messiah. Their ‘spirituality’, their effort to let this yearning emerge to a full pilgrimage to the Crib, was the first step. The celestial beings ‘came to hear novelties’ of their Biblical advent. Actually, all of us, angels and humans; and animals, and other inanimate beings are joining in God’s own ‘spirituality’. That is, we gather around his reading and creating the ‘fullness of time’; his judging of the human condition; and his effort to make the Incarnation come about… On this holy eve we all share the role of interpretation of the Nativity.

Joseph the tzadik

The figure of Joseph in our icon is puzzling. His posture, traditionally, is interpreted as an expression of doubt. His is bent under the weight of a heavy test. Is the birth of his son Divine or someone else is the father? He is almost in a dreaming position: half conscious, half asleep. This recalls his previous dream when the angel of the Lord appeared to him. ‘But while he thought on these things [to dismiss Mary privily], the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream, saying, Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost.’

We Christians know very little of Joseph. This icon, however, invites us to see him within the Judaic tradition, in terms of a tzadik, a righteous man. He proved to be a righteous man when his faith was tested by this birth.

His response to the Dream (and to the test) is a ‘second Annunciation-scene’. Mary was greeted by an Angel with the message that she had been chosen to be the Mother of the Messiah. Joseph’s test of faith, his own yes to the angelic guidance is indeed a parallel to the Annunciation. His response complements Mary’s fiat. Mary’s position in the icons, turning towards Joseph while semi-laying on her bed, is an expression of this.

There is a further interesting detail, which we can connect to this interpretation. The figure of the old shepherd, traditionally, is interpreted as a ‘tempter’, who wants to raise human doubts about the birth. His bent figure, however, is almost parallel with the bending of the Angel at the top on the right side. This is the hidden expression of Joseph’s righteousness. He is indeed a tzadik: he can see God’s Angel with a message where others could see only the Tempter. This bottom left hand corner in the icon shows the Joseph-scene almost like an off-stage event. Yet, it is a spiritual co-centre of the icon. There was no rebellion in him at a decisive point in human history.

02.01.2017

The figure of Joseph in our icon is puzzling. His posture, traditionally, is interpreted as an expression of doubt. His is bent under the weight of a heavy test. Is the birth of his son Divine or someone else is the father? He is almost in a dreaming position: half conscious, half asleep. This recalls his previous dream when the angel of the Lord appeared to him. ‘But while he thought on these things [to dismiss Mary privily], the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream, saying, Joseph, thou son of David, fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost.’

We Christians know very little of Joseph. This icon, however, invites us to see him within the Judaic tradition, in terms of a tzadik, a righteous man. He proved to be a righteous man when his faith was tested by this birth.

His response to the Dream (and to the test) is a ‘second Annunciation-scene’. Mary was greeted by an Angel with the message that she had been chosen to be the Mother of the Messiah. Joseph’s test of faith, his own yes to the angelic guidance is indeed a parallel to the Annunciation. His response complements Mary’s fiat. Mary’s position in the icons, turning towards Joseph while semi-laying on her bed, is an expression of this.

There is a further interesting detail, which we can connect to this interpretation. The figure of the old shepherd, traditionally, is interpreted as a ‘tempter’, who wants to raise human doubts about the birth. His bent figure, however, is almost parallel with the bending of the Angel at the top on the right side. This is the hidden expression of Joseph’s righteousness. He is indeed a tzadik: he can see God’s Angel with a message where others could see only the Tempter. This bottom left hand corner in the icon shows the Joseph-scene almost like an off-stage event. Yet, it is a spiritual co-centre of the icon. There was no rebellion in him at a decisive point in human history.

02.01.2017

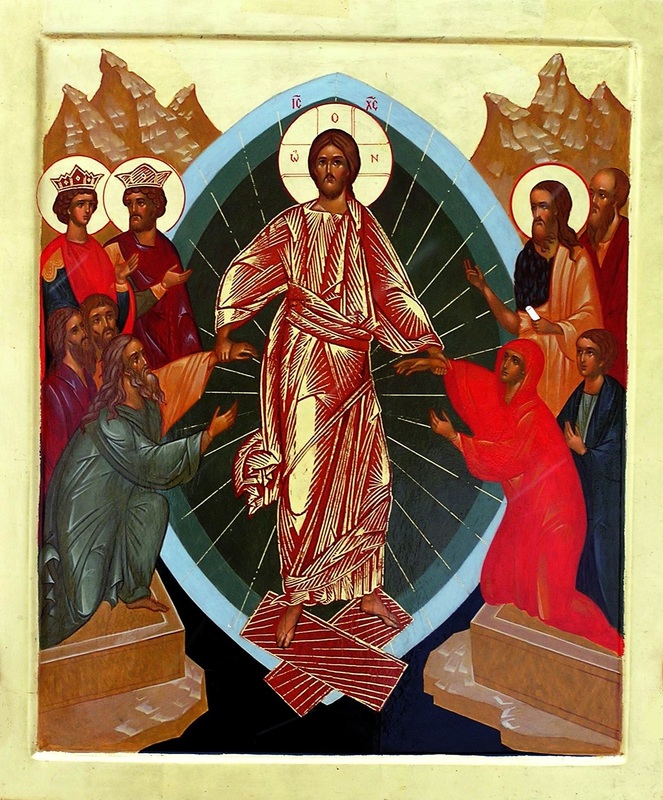

The Icon of the Resurrection

Proudly powered by Weebly